Financial risks can seemingly come out of nowhere. Think about how many on Wall Street were caught off guard by the 2008-09 financial crisis or even the volatility of a few weeks ago. Yet the potential risk emanating from the packaging of bad mortgages was in plain sight, but ignored.

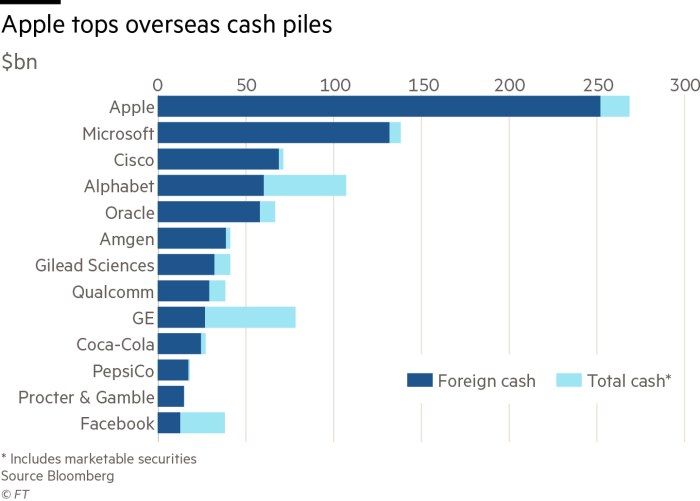

Today, there is another financial risk lurking in plain sight. It lies in the vast overseas holdings of technology giants like Apple (AAPL), Alphabet (GOOG), Microsoft (MSFT) and many others.

I discussed this topic to my subscribers in the October issue of Growth Stock Advisor. But since there is so much misunderstanding about the roughly $1 trillion (or possibly as high as $2 trillion) in funds held overseas by U.S. multinationals, I wanted to clear it up for you.

I know there is much misunderstanding about this subject just from gleaning the comments section on several recent articles published by The Wall Street Journal. Apparently, Americans are under the impression that this $1 trillion is just sitting in bank accounts overseas and that both the overseas banks and host countries don’t want to lose control of this money. Nothing could be further from the truth. Let me explain…

The New Force in Global Bond Markets

I want you to think about it for a moment, and it will make sense. Over the past decade, the largest U.S. companies have built up cash piles of as much as $2 trillion, rising more than 50% in that time period. Why would these firms let all that cash sit there idly, parked in a bank account?

Well, they haven’t. Instead, these aforementioned technology companies – they control about 80% of the overseas hoard – and other U.S. multinationals have put the money to work by snapping up all sorts of bonds. The purchases have mainly been the bonds of other corporations, but government bonds have also been bought.

In fact, companies like Apple, have actually issued their own low interest rate bonds and then used some of the proceeds to invest into the higher-yielding debt of other firms. In some cases, it has taken a large anchor position in certain offerings à la an investment bank like Goldman Sachs. In effect, it has become one of the world’s largest asset managers.

According to the Financial Times, thirty of the top U.S. companies have more than $800 billion worth (mainly short- and medium-term) of fixed-income investments. The breakdown is as follows:

- $423 billion of corporate debt and commercial paper (very short-term corporate debt)

- $369 billion of government and government agency debt

- $40 billion of asset and mortgage-backed securities

- $10 billion of cash

Those 30 aforementioned companies have accumulated more than $400 billion worth of U.S. corporate bonds. That is nearly 5% of the $8.6 trillion market. Apple itself owns over $150 billion of corporate bonds, more than most asset managers. And Microsoft owns over $112 billion in government securities.

This should not come as a shock to students of history. Some of the banking industry’s most venerable names started out in other businesses. The Rothschilds were merchant traders that became the most powerful banking empire in Europe. As Mark Twain is reputed to have said, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.”

The Risk to the Bond Market

I now want you to think about this scenario… let’s say most of these companies bow to political pressure and bring “home” this overseas hoard.

That would mean selling a lot of corporate and government bonds. The likely result would be a massive spike higher in interest rates. Just look at how poorly the market acted when there was just a hint of a tapering of purchases by the Federal Reserve. A massive unloading of bonds could quickly turn into a nasty market event starting in the bond market and quickly spreading to the stock market.

Ironic, isn’t it? A massive tax cut and ‘patriotically’ bring money back to the United States could end up being the trigger event for a recession caused by much higher interest rates.

Luckily, from what most of the technology companies (with the exception of Apple) have said in their latest conference calls, they are making no major plans to sell their bond holdings.

Microsoft – with the second biggest pile held overseas – said it had already been able to make all the investments it wanted under the old tax regime, and didn’t expect anything to change as a result of the law. Alphabet said, “There’s no change in our capital allocation.”

What It Means to You

As market participants, I think we should all breathe a collective sigh of relief. As of the moment, nothing has changed and you should just stick to your current investment plan.

But what if the political pressure heats up and these tech companies wilt and decided to liquidate their bond holdings?

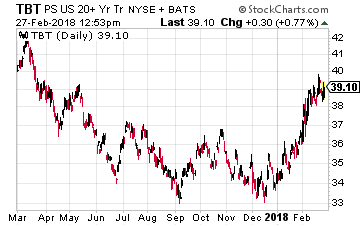

Then putting money into the ProShares UltraShort 20+Year Treasury ETF (NYSE: TBT) would make a lot of sense. This ETF uses futures and swaps to correspond to twice the inverse of the ICE U.S. Treasury 20+Year Bond Index.

Then putting money into the ProShares UltraShort 20+Year Treasury ETF (NYSE: TBT) would make a lot of sense. This ETF uses futures and swaps to correspond to twice the inverse of the ICE U.S. Treasury 20+Year Bond Index.

It is up 15% year-to-date thanks to the recent bond market scare, but is little changed over the past year.

Since most of the tech companies own a lot of corporate bonds, and if you have a high risk tolerance, you could short corporate bonds ETFs such as the Vanguard Long-Term Corporate Bond ETF (Nasdaq: VCLT), which is down 4.7% year-to-date and the SPDR Barclays High-Yield Bond ETF (NYSE: JNK), which is down 0.6% year-to-date.

But only think about these trades if and when the technology companies begin liquidating their holdings. I do not think that will happen any time soon, but stay tuned.

— Tony Daltorio

Imagine having 12 new monthly income checks, carrying the potential of up to 21% yields.This is possible because of a tested strategy to get paid out regularly, like a paycheck. For over a decade, I have helped more than 26,000 investors secure 12 new monthly payouts. Meaning, you know exactly how much you'll make every month... Because of some stocks that pay us 8%,13.4%, and even 21.6% yields. See it for yourself here.

Source: Investors Alley