Back during my business school days, in an economics class at the Rochester Institute of Technology, my professor told us about a concept known as the “Paradox of Thrift.”

The Keynesian theory – which I’m intentionally oversimplifying – basically tells us that a boost in autonomous savings is actually bad for the economy, since it leads to lower demand, lower gross output, and ultimately, a drop in aggregate savings.

The fact that saving money is bad for the economy is counterintuitive, hence the “paradox” label.

Today I want to tell you about another “paradox” – one that initially seems just as contradictory.

I call this one the “Paradox of Wealth.”

And it applies perfectly to the “Infection Correction” – the name I coined for the coronavirus-fueled sell-off that’s wiped away trillions in shareholder wealth over the last few weeks.

This is the worst run for stocks since October 2008 – in the depths of the Great Financial Crisis. I believe it will get worse – perhaps much worse – before it gets better.

But as we’ve been telling you, that’s not a reason to panic.

Just the opposite, in fact – thanks to the Paradox of Wealth.

You see, as counterintuitive as this sounds, big sell-offs can be your biggest long-term wealth-building opportunities.

I know that idea’s not always easy to digest. And while I don’t want to downgrade the seriousness of the current situation, I want to reassure you it will be OK.

What will set you apart from the masses is making deliberate moves in times like these that will be best for the long run.

That’s why I want to share with you the tale of an investor who turned one of the worst periods in modern history into one of the smartest wealth-building moves of all time…

The “Billionaire’s Story”

Most folks today associate the late Sir John Templeton with the mutual fund family that carries his name – and with good reason, since he was a pioneer of the industry.

Templeton Growth Fund Inc. (TEPLX) was established in 1954. In the 1960s, it was one of the first funds to invest in Japan, allowing its shareholders to cash in on that country’s economic renaissance.

Templeton’s work made him a multibillionaire. And his philanthropic efforts – in excess of a billion bucks – have had huge beneficial effects.

But as a lifelong contrarian investor who co-authored a Prentice Hall book on the topic, I’ve always admired Templeton for a move he made long before his mutual fund efforts.

There’s an old French proverb that says “Buy on the cannons, sell on the trumpets.” A less poetic variation is “Buy when there’s blood in the streets, even if the blood is your own,” attributed to 18th century British nobleman and banker Baron Rothschild.

At one of the world’s darkest times, that’s just what Templeton did.

In September 1939, with the Great Depression still gagging the U.S. economy, Germany invaded Poland, starting World War II. At first, U.S. stocks rallied on hopes that American companies would profit by providing war materials.

That giddiness ended when Adolf Hitler’s panzers rolled into the Low Countries of Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands in May 1940.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged from its euphoric peak of 155 all the way down to 111 – a freefall of 28% – by June 1940, before it temporarily stabilized.

Rumors swirled that the stock market would be shuttered for the duration. (In fact, an early June issue of Time magazine featured an article under the headline “Stock Market to Be Closed?”)

But where most investors feared the very worst, Templeton saw the long-term opportunity…

He scraped together $10,000 (borrowing some of it) to buy 100 shares of all 104 New York Stock Exchange companies that were trading for less than $1 a share ($17 in today’s money) – including some that were bankrupt.

Templeton knew that some companies would implode, but he guessed that most would survive and many would even thrive.

He was right.

Stocks are “discounting” mechanisms, meaning their valuations are based on expectations of the future. And the Dow started its rebound at roughly the same time the Allies seemed to achieve a turning point in the war.

In April 1942, Jimmy Doolittle’s Tokyo Raiders got some payback for Pearl Harbor by bombing the Japanese mainland for the first time. Two months later, the U.S. Navy pulled off a decisive victory against Japan at the Battle of Midway – putting the Allies on the offensive for the rest of WWII.

From its bear market bottom of 92, the Dow rebounded – slowly at first, and then more strongly.

The blue-chip index reached 119 by the end of 1942 and 142 by D-Day in June 1944.

Over the next 24 years, the Dow rocketed six-fold – or nearly 900 points – making Templeton look brilliant.

As dour as the possibility of a coronavirus-fueled bear market and economic recession might seem to us at the moment, let’s put things in the proper context: It’s nowhere near as frightening as the most destructive conflict the world has ever seen.

Templeton’s bet – in the face of such daunting uncertainty – led to a massive payoff.

And we believe the same opportunity holds true now.

The more news I see about the coronavirus pandemic, the more I believe the “Infection Correction” will get worse before it gets better.

Perhaps even much worse.

But that doesn’t mean your long-term wealth building is in trouble. Far from it.

The biggest market pullbacks of all time show us that’s true…

When Bad Markets Lead to Good Things

I’ve never met Ben Carlson, portfolio manager at Ritholtz Wealth Management. But I dig his thinking.

To give folks some perspective on what could happen in the months to come, Carlson took a long look at some of the biggest pullbacks of the last hundred years. And his findings dovetail perfectly with my “Paradox of Wealth.”

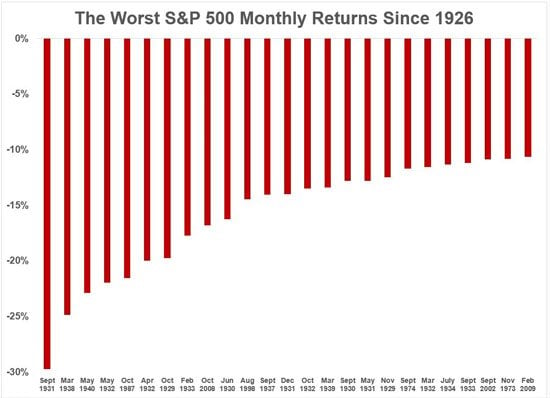

According to MarketWatch.com columnist Shawn Langlois, some of the worst pullbacks were part of stock market infamy – like the Great Depression, Black Monday, and the Great Financial Crisis (see accompanying chart).

Sources: Ritholtz Wealth Mgmt, Wealth of Common Sense, and MarketWatch.com.

Sources: Ritholtz Wealth Mgmt, Wealth of Common Sense, and MarketWatch.com.

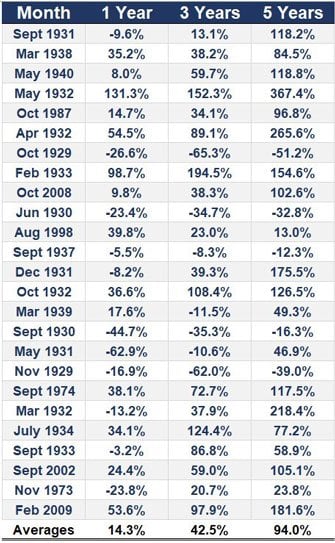

But here’s the good part, Carlson told MarketWatch, “Fifty-six percent of the time stocks were higher one year later. Seventy-two percent of the time they were higher three years later. And they were higher 80% of the time five years later.”

The following chart – from Carlson’s “Wealth of Common Sense” blog – provides detailed evidence of this assertion.

The bottom line: Barring a Great Depression, these results show that after a huge down month for stocks, the odds are strong your investments will be much higher one year, three years, and five years after the fact.

How to “Accumulate” the Best Stocks

The key, Carlson says, is that you need to be willing to buy in at several points during and after the big sell-off.

I like that because it’s essentially the “Accumulate” strategy I advocate. That means you establish a foundational position in a stock that you like and then add to that stake on pullbacks or as you get additional cash.

“Every investor’s told to buy low and sell high,” he told his readers. “But most don’t realize that buy low typically works out to buy low, then buy lower, then buy even lower, and once you really hate yourself, buy lower than you thought was possible.”

That’s the Contrarian Investing mindset.

In a separate (and unrelated) research note, Howard Marks – a billionaire investor and co-chair of Oaktree Capital Management – offered a neat bit of perspective on how to get yourself to buy in such uncertainty.

In a whipsawing market like this one, Marks wrote that “no one can tell you this is the time to buy [stocks]” because “nobody knows.”

Marks said that “some buying” right now isn’t a bad idea, “because things are cheaper. But there is no logical argument for spending all your cash, given that we have no idea how negative future events will be. What I would do is figure out how much you’ll want to have invested by the time the bottom is reached – whenever that is – and spend part of it today.”

That’s the essence of the “Accumulate” strategy: Decide how much of a stock you want to own, then average into it over time.

That’s especially strategic following a big sell-off.

And that, my friends, is the “Paradox of Wealth.”

— William Patalon III

Source: Money Morning