Recessions are an economic reality. They’re also difficult to predict with any precision; they typically start before anyone even knows they’re happening and end before economists have enough data to know they’re done.

Moreover, they’re also usually pretty short. Since the end of the Great Depression, there have been 13 recessions in the U.S., and 9 of those were less than one year in duration.

But the individual impacts of a recession can be much bigger and longer lasting, causing permanent financial damage to those who aren’t prepared to ride out the short-term implications and quickly get back on their feet.

Millions of Americans still haven’t recovered from the Great Recession (2008-2009). Many never will.

Put it all together, and taking steps to protect yourself and your family from the potential consequences of a recession is not only important but necessary. Let’s take a closer look at what a recession is, how it’s measured, and what you can do — starting today — to make sure you’re as prepared as possible for the next recession.

What is a recession?

A recession is generally considered a slowdown of economic activity as measured by GDP (gross domestic product) lasting two consecutive quarters or longer. The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) has a more expansive definition of recession:

A recession is a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales. A recession begins just after the economy reaches a peak of activity and ends as the economy reaches its trough.

The NBER measures economic activity as more than just GDP and doesn’t require two straight quarters of decline to mark the beginning of a recession. The Great Recession offers an interesting example of why this matters. According to the NBER, GDP declined in December of 2007 and the first quarter of 2008 but grew in the second quarter before declining again in the third and fourth quarters of 2008 and the first quarter of 2009.

This may seem like a distinction without a difference, particularly since it’s often used after the fact to identify periods of recession and recovery. To some extent, that’s true; these measures don’t do much good to address a recession that’s already happened. On the other hand, the research into recessions and the various measures that can identify when the economy is slowing or is at risk of recession can help economists and policy makers more quickly and effectively address future recessions.

Historically, recessions have lasted about a year and a half on average, but more recently, they have tended to be shorter. Since 1945, the average recession in the U.S. has lasted less than one year.

What are the real-world implications of a recession?

Looking beyond the dry textbook definition, recessions mean real economic harm. Moreover, the end of a recession is marked by a return to economic growth, not the full recovery of the economy to prerecession levels. In other words, people affected by a recession often continue to struggle long after economists have said the recession is over.

For example, the U.S. suffered a relatively mild recession in 1990 and 1991 that only lasted eight months and saw GDP decline a mere 1.4%. But while the economy returned to growth, unemployment continued to rise for a full 16 months after the recession technically ended, peaking at 7.8%. We saw a similar trend in the recession of the early 2000s, when the jobless rate peaked more than a year and a half after the end of the recession.

The job losses from the Great Recession are a powerful example of how long individual struggles following a recession can last. On a technical basis, the economy returned to growth in the second half of 2009, and the unemployment rate peaked four months later. That’s a relatively “quick” period for unemployment to peak and return to job creation. Sure, it was good that jobs were being created again, but the unemployment rate peaked at 10%, fully double the rate when the recession started.

Moreover, unemployment would remain at or above 9% for two more years and didn’t return to the prerecession rate of 5% or below September of 2015. That’s six years of high unemployment. In other words, even though the recession was technically over, a slow jobs recovery meant millions of Americans continued to struggle mightily.

The implications of protracted high unemployment are many. Median household income rates show just how much impact the weak and slow recovery had:

Data Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Median U.S. household income fell nearly 10% in the aftermath of the Great Recession, a direct result of the unemployment rate being nearly double the historical average for a protracted period of time. Moreover, a large portion of the population identified as being “underemployed,” having taken a job with far lower pay earned or fewer hours than they worked prior to the recession.

How could this look on an individual basis? Let’s say you’re an average American, between 45 and 54 years old, who’s married with kids. Today, you have about $50,000 saved toward retirement (according to Vanguard’s How America Saves 2019) and just under $16,000 in savings, according to Bankrate.com. If you’re younger or single, chances are you’ll have far less.

Simply put, $16,000 in savings — far more than millions of us have saved — won’t cover the food, shelter, and transportation expenses for most families for more than a few months.

How far would you be able to stretch your existing savings, along with any unemployment benefits, if you lost your job? Moreover, would you be able to avoid tapping retirement savings before you ran out of cash or found new work? Remember, you’ll pay a 20% penalty for early withdrawals from most retirement accounts — plus pay income tax, too — so today’s balance would go a considerably shorter distance in the real world. That’s assuming it doesn’t decline; remember, the stock market usually falls sharply during a recession.

Now that you’ve considered your own situation, how financially prepared are you for the next recession?

The first two things to do to prepare for a recession

When it comes to preparing for unexpected financial events, there are two things you can do that will have the biggest impact on your ability to ride it out and emerge unscathed on the other side. The two things you need to do first are:

- Build up emergency savings.

- Pay off high-interest debt and keep other debt to a minimum.

Let’s take a closer look at why these are by far the two most important things everyone should do first.

Build up emergency savings

This is the most obvious step to take, and it’s one that you’ve surely seen in every other financial-preparedness article you’ve read so far. What may not be so clear to you is how much you should have saved. There isn’t a single answer to that question that fits everyone, but there are some pretty good basic guidelines to follow.

In general, it’s recommended that you have at least six months’ expenses in savings. This means enough money to cover your housing and utilities, basic necessities like food and personal care, and other financial obligations like auto loan and insurance payments.

And while you’ll find some wiggle room (you can adjust the thermostat to cut energy use and eliminate eating out, and you’ll save money on transportation if you’re not commuting) to cut expenses if you find yourself without a job or if your income falls, a lot of recurring expenses are relatively fixed in cost. Moreover, some expenses — such as health insurance — often go up if you lose your job, since you no longer have an employer covering some of the cost.

In other words, take the time to develop an accurate measure of what your expenses would really be if you were to lose your job.

The next step is to gradually build up your safety net. It may take a year or even longer to save up enough cash to reach the six-months-in-savings mark. That’s OK; just set the goal and put a plan in place to reach it. Once you get to six months, keep saving with a goal of one year in savings. That’s particularly true if you own a home or have dependents living with you. The reality is, in those situations, your financial liabilities are higher, and you want to have the resources at hand to deal with the unexpected.

Frustrated that your emergency savings hardly gets any yield? Time to let that go and think about it this way: Would you only buy a life preserver that also functions as a tuxedo jacket? As awesome as that would be, no. The purpose of emergency savings is to be there in an emergency, not to get sexy returns. Sure, you should stick it in the bank account that will deliver the best yield; just don’t go buying high-yield stocks because you can’t get a 3% interest rate from your bank.

Keep debt to a minimum (and pay off high-interest debt ASAP)

Debt can be a wonderful financial tool when used responsibly. For instance, buying a home or an automobile without a loan is impossible for most of us. Moreover, taking advantage of low-interest (or even zero-interest) financing to buy an appliance or other big-ticket item is also a smart use of someone else’s money. Personally, I’m also a big fan of credit card rewards programs; getting cash back at the gas station or local warehouse store for everyday items is a no-brainer to me.

When debt is damaging — especially during a recession, when your financial resources may be more limited — is when it’s expensive and not beneficial. For instance, using credit cards to buy items you don’t have the cash to purchase and not paying them off at the end of the billing period is one of the most financially destructive actions you can take.

Here’s an example. The average credit card interest rate is nearly 17%. If you charge $1,000 to the average card and only make the minimum payment (typically 2% of the balance or $25 minimum), a handy credit card calculator tells us you’ll end up spending $1,486 over five years to pay that $1,000 purchase off.

By paying off high-interest debt and keeping other debt to a minimum (pro tip: buy a car and keep it; don’t lease a new one every few years), you’ll do yourself and your financial situation two big favors:

- You will spend less money to acquire the things you buy (and buy less stuff you don’t need).

- You will reduce your monthly expenses, meaning you won’t have to set aside as much money for emergency savings.

Three more things that can help you prepare for a recession

Once you’ve implemented a plan to build up emergency savings and pay down debt, it’s time to start taking actions that could go even further toward improving your long-term financial future:

- Maximize your professional value.

- Build your portfolio based on your goals and not on the market’s behavior.

- Implement a plan to help you profit from a market crash.

Let’s take a closer look at each of these items.

Maximize your professional value

One of the biggest struggles many people have faced since the last recession has been regaining similar levels of employment and income. In addition to the loss of opportunity as many companies went under or downsized, many businesses have learned how to do more work with fewer employees and leveraged technology and automation to reduce labor needs.

Many of the fastest-growing fields need workers with skills and training that may not have even existed when you were in school, and the kind of work you currently do may not be as important or necessary as it was in the past. If that’s the case for you, it may be time to take steps to make yourself more valuable.

This could include adding new certifications or training in your current profession to increase your value to your employer (or even a competitor), or it might be time to explore a job change to a high-demand field while the economy is in good shape and there’s opportunity. Sure, it can be scary walking away from the known factor of your existing job, but the best time to make a change is when you have the leverage of ongoing employment and the support of a healthy economy. Simply put, it’s easier to find a better job in a good economy than to find any job during or right after a recession.

Build your portfolio for the long term

Take a look at the chart below, which shows how the market tends to drop during recessions:

^SPX DATA BY YCHARTS.

Since 1990, the U.S. has experienced three recessions, and each time, the stock market fell more than 10%. In the two most recent recessions, the stock market lost more than 30% of its value from the peak to the bottom. The thing is, this is completely normal during most recessions.

Moreover, it’s also completely normal for the market to recover relatively quickly, too.

Unfortunately, one of the biggest mistakes people make during a recession is to sell their stocks or stock-based mutual funds, often after the market has already fallen sharply, expecting it to fall even more. Sadly, this rarely results in savvy “buying at the bottom” for most people. More often, the stock market starts to recover before people are ready to reinvest, resulting in them missing out on the market’s recovery.

Portfolio allocation to protect your wealth

As the graph above shows, the stock market does fall during recessions (and often at other times when there’s not a recession). These declines can happen quickly and unpredictably; even the best investors often don’t see them coming. Moreover, the recovery — when the stock market starts going back up — is just as unpredictable. This is why you’ll never guess your way around the “bottom” of the market; more likely, you’ll just sell near the bottom and sit on the sidelines, watching the market go back up, anchoring on the low price you sold at.

The takeaway isn’t to avoid stocks. To the contrary, the chart above demonstrates why you should own stocks, but only with a long-term time horizon. Think five-plus years or, better yet, decades. By taking a “buy and hold” approach, you won’t make the mistake of selling at the worst time and missing out on the market’s recovery.

It has often been said that the short-term risk of stocks, the volatility we see during times of uncertainty, is the “price of admission” to invest in the stock market. If you can sit on your hands and not sell at every sign of a downturn, it’s a price you won’t have to pay. One of the best ways to make it easier to not sell during the next recession is to put a portion of your portfolio in low-volatility investments, such as bonds. The difference between stocks and bonds is that with stock, you are part owner of a company, while a bond is a loan.

This difference is why stocks and bonds vary greatly in volatility. Simply put, the value of a bond is very easy to measure: the dollar amount of the bond plus the amount of interest it will yield before maturity. So long as the entity issuing the bond remains solvent, the bond will remain stable in value.

Stocks, on the other hand, are more speculative in nature, with people varying greatly in what they may think a particular business is worth. Add the uncertainty of a recession to the mix, and people often overreact in fear and decide to sell their stocks at what eventually proves to be a bargain price. Owning bonds is a great way to hedge your risk from that volatility for the part of your portfolio you may need to sell in the next few years.

Why not just own all bonds, you ask? Bonds are more stable in value as an asset class, but the persistent low-interest-rate environment we’ve been in for the past decade also makes them a low-return asset to own for the long term.

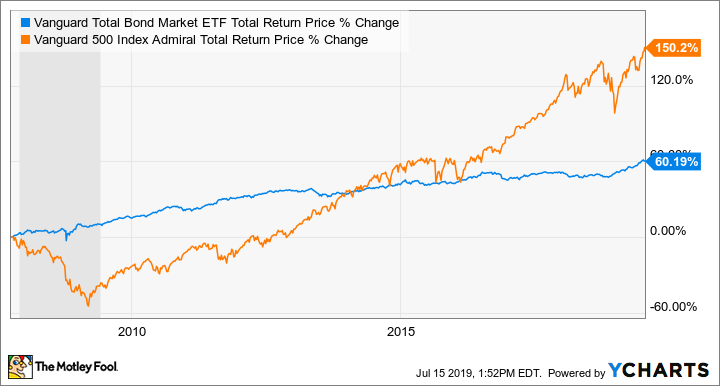

Owning bonds will help you avoid the short-term drops, but you’ll miss out on all the long-term gains, too. Here’s a chart to demonstrate:

BND TOTAL RETURN PRICE DATA BY YCHARTS.

The chart above starts in October 2007, which was when the stock market peaked before the Great Recession. So while bonds — represented by the Vanguard Total Bond Market ETF (NASDAQ:BND), a diversified mix of investment-grade corporate and U.S. Treasury bonds — proved the superior “loss-avoidance” investment for a few years during and immediately after the recession, stocks — represented above by the Vanguard S&P 500 Index Fund (NASDAQMUTFUND:VFIAX) — have proven the far better long-term holding, delivering more than double the returns of bonds.

So what’s an investor to do? Consider your short- and long-term goals, and invest accordingly. If you are going to need to access some of your investments starting in the next few years, you should invest those resources in high-quality bonds. You may miss out on some of the upside of stocks, but you won’t get caught flat-footed during a recession or market crash with all your eggs in a volatile basket of stocks.

In general, the further you are from retirement, the less you should allocate to bonds. But as you get closer to retirement (or paying for a kid’s college or some other financial goal), you should gradually increase your allocation of bonds.

For younger investors, that may mean not owning any bonds just yet — at 42, I have a bond-free portfolio — so long as you can avoid selling when the market crashes.

Have a plan to buy during a recession

While market drops are often tied to real-world crises such as recessions that come with real-world implications, they also give us some of the best opportunities to buy stocks. For this reason, it may be helpful to set aside a small amount of cash in your investing account or retirement account so you can act when the market drops.

What’s a reasonable amount? A number of factors can make it very different from one person to the next, including the size of your portfolio, whether you’re still working and regularly putting new money in your accounts, and how close you are to retirement or some other financial need. But in general, having 5% of your portfolio specifically earmarked to invest when the market falls a certain amount is a reasonable level. That may be a little more or a little less, depending on your personal preferences as much as on any hard-and-fast rules.

It’s not a good idea to reserve all of your buying for market crashes. Taking that kind of action would cause you to have spent most of the past decade building up and sitting on your cash while the market continued to march higher and higher. Think about it this way: If the S&P 500 fell by 50% from current levels, it would still be 25% higher than it was when the market peaked before the Great Recession.

It’s also helpful to implement some guidelines to help you know when to act. Two reasonable times I’ve identified to opportunistically invest your spare cash are at 20% and 30% market drops.

Why 20% and 30% drops? Because on average, the market falls 20% about once every four years, while we see a 30% drop about once a decade. That means they’re both frequent and meaningful enough to make them worth setting some cash aside for.

For instance, the S&P 500 fell about 20% from early October to December 24, 2018, while the NASDAQ Composite fell even further:

^SPX DATA BY YCHARTS.

Six months later, both indices had fully recovered those losses, and investors who acted quickly during the sell-off enjoyed strong — and quick — gains:

^SPX DATA BY YCHARTS.

But since Mr. Market doesn’t always stop at 20% and start marching upward again, reserving some of that “dry powder” for a bigger sell-off can be worthwhile.

For instance, during the Great Recession, the S&P 500 first fell 20% from October 2007 to July 2008. But unlike the more recent bounce-back in 2018-2019, the market fell another 45% before finally reaching bottom on March 9, 2009. In all, the S&P 500 lost almost 60% of its value from October 2007 to March 2009.

^SPX DATA BY YCHARTS.

Keeping half of your market-crash money ready to deploy in a deeper market correction can serve two purposes. The first and most obvious is that it gives you the chance to take advantage of an even more deeply discounted stock market and enjoy bigger long-term gains when things inevitably improve. The second purpose may be even more important: It can help you manage your emotions and avoid falling into the trap of selling because you think you need to do something.

What should you do if the market falls more than 30%? Using history as our guide, we can predict that it probably will fall by 40% sometime in the next 30 or 40 years. At some point during the next century, it’s likely going to once again lose half or more of its value, too. Personally, I don’t keep extra cash set aside for these occurrences because they happen so rarely. You’ll lose out more in opportunity cost — how much the market goes up before it falls — to make it worthwhile.

However, if your concern is managing your emotions and having a plan to help keep you from selling, it might be worth setting aside a small amount of cash to deploy at 40% or even 50% declines. Again, I wouldn’t suggest it be a very large amount; the market will likely be triple in value from today’s prices before we see another 50% decline.

Prioritize, plan, and act

I can’t tell you when the next recession will happen with any accuracy. Neither can the TV pundits or even the best economists. But we know that it will happen again. Real businesses will fail. Real people will lose their jobs and sell their stocks after the market crashes.

It’s also true that many of us will sail through the next recession generally unaffected. Yet at the same time, the risk of permanent financial harm — millions of baby boomers will never be able to fully retire because of the Great Recession — is simply too great to do nothing.

Start with a plan based on your individual situation, prioritizing the following things:

- Building up emergency savings and paying off expensive debt

- Maximizing your professional value and prospects

- Allocating your portfolio based on your goals and not on how the market is doing right now

Your priorities and the plan you make will be unique to you. But once you put it into action, it should help you minimize the harm from a recession, bounce back quickly, and even grow your wealth. The simple act of putting a plan into action — giving yourself something to do — will improve your prospects of coming out of the next recession unscathed.

— Jason Hall

Motley Fool Stock Advisor's average stock pick is up over 350%*, beating the market by an incredible 4-1 margin. Here’s what you get if you join up with us today: Two new stock recommendations each month. A short list of Best Buys Now. Stocks we feel present the most timely buying opportunity, so you know what to focus on today. There's so much more, including a membership-fee-back guarantee. New members can join today for only $99/year.

Source: The Motley Fool