Founded in 1945 in Bentonville, Arkansas, Walmart (WMT) is the world’s largest retailer and operates on a truly staggering scale. For example, its 2.2 million employees serve 275 million consumers per week in 27 nations via a network of more than 11,000 stores that collectively sell over $500 billion of merchandise per year.

Approximately 50% of Walmart’s stores are located in international markets, which the company entered in 1991.

These locations serve about 100 million customers per week under 56 different banners (store brands).

While Latin America, the UK, and Canada are important regions, the majority of Walmart’s sales and profits are derived from the company’s U.S. stores (64% of revenue) and Sam’s Club (12%).

Walmart sells just about everything in its stores. Grocery (56% of U.S. sales) is Walmart’s biggest merchandise category, followed by health & wellness (11%) and general merchandise (32%).

Walmart has its own private-label store brands, but branded merchandise still represents a significant portion of total sales. The company’s general strategy is to be the low-price leader in its categories.

In addition to its significant brick-and-mortar operations, Walmart has fast-growing e-commerce websites operating in over 11 countries. Walmart.com averages more than 80 million unique visitors a month and offers millions of products that can be shipped or picked up at one of Walmart’s many physical locations.

E-commerce sales account for about 5% of the company’s total revenue today but will continue growing in importance as Walmart invests less in new store openings and more in its digital operations, supply chain, and logistics.

With 45 consecutive years of dividend increases behind it, Walmart is a dividend aristocrat and will become a dividend king in 2024.

Business Analysis

Walmart’s retail dominance is supported by several factors. Most notably, the company prides itself on its “everyday low price” strategy, which has been its guiding mantra since its founding.

This intense focus on low cost is made possible by Walmart’s biggest competitive advantages, which are predominantly its substantial size, economies of scale, and the nation’s largest distribution and logistics network.

The company has spent over 50 years and tens of billions of dollars building, adapting, and perfecting its massive store network. In a highly competitive, low-margin industry like retail, few rivals have the financial resources or patience to try to replicate the company’s dominant supply chain.

For example, Walmart’s nearly 6,000 stores in the U.S. are located within 10 miles of 90% of the population. These locations are served by a logistics network that:

- Sources products from more than 100,000 suppliers in over 100 countries

- Has over 150 distribution centers which average over 1 million square feet

- Utilizes 30 e-commerce fulfillment centers

- Runs a fleet of more than 6,100 trucks, 61,000 trailers, and 7,800 drivers

- Has each distribution center support 90-plus stores within a 150-mile radius

Another key factor to Walmart’s success (and why it’s been able to become a dividend aristocrat with 45 consecutive years of payout increases) is the company’s adaptability.

For example, in 1987 Walmart concluded that it had largely saturated the U.S. market with its traditional discount centers, which average more than 100,000 square feet. As a result, the company decided to break into the U.S. grocery market via the launch of Walmart Hypermarts.

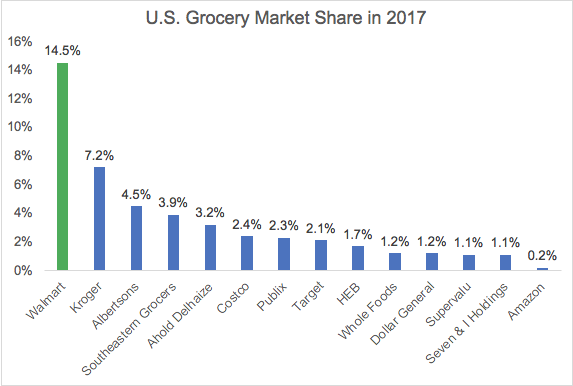

The success of Hypermarts led Walmart to roll out its modern Supercenter stores, which averaged around 180,000 square feet since they combined groceries and general merchandise. These, in turn, transformed Walmart into America’s largest grocer with about double the market share of its nearest competitor, Kroger (KR).

Source: GlobalData Retail Estimates, Simply Safe Dividends

Source: GlobalData Retail Estimates, Simply Safe Dividends

Supercenter stores with a strong focus on grocery items, which draw predictable traffic, also increased Walmart’s product turnover, resulting in better sales per square foot than rivals like Target (TGT).

- Costco (COST): $1,200 per square foot

- Walmart: $430 per square foot

- Target: $290 per square foot

Costco’s much larger sales per square foot are the result of its wholesale warehouse business model, in which customers pay a membership fee and buy relatively large quantities of low-cost goods.

Walmart has also copied the Costco model with the 1983 founding of Sam’s Club ($100 per year annual membership), which now has nearly 600 stores across the world and generates 12% of the company’s sales.

Further evidence of Walmart’s adaptability can be seen in the company’s launches of international stores (starting in 1991), as well as its 1998 concept, the Neighborhood Market, which is a much smaller store (averages 42,000 square feet versus 178,000 for a Supercenter) designed to miniaturize a Supercenter but for urban markets.

The Neighborhood Market concept is appealing because urban areas have traditionally been impractical for giant big box stores due to their density, high real estate prices, and zoning regulations.

Of course, what many investors have been worried about in recent years is the threat that e-commerce, especially Amazon (AMZN), might pose to the company. That’s understandable as Walmart suffered through several years (starting around 2014) of declining same-store sales, falling revenue, and shrinking earnings.

However, management has done a good job of adapting the company’s business model yet again, with a strong focus on integrating online sales into its massive existing store base.

For example, in 2016 Walmart bought Jet.com, a leading online retailer, for $3.3 billion. The deal brought with it Jet.com founder Marc Lore, who became Walmart’s head of online retail. Lore instituted a flurry of secondary acquisitions and joint ventures with various e-commerce giants to quickly ramp up Walmart’s competitive position in online retail.

Source: Walmart Investor Presentation

Source: Walmart Investor Presentation

In mid-2018, for example, Walmart invested another $500 million into its partnership with JD.com, a major Chinese online retailer which Walmart now owns a 12% stake in.

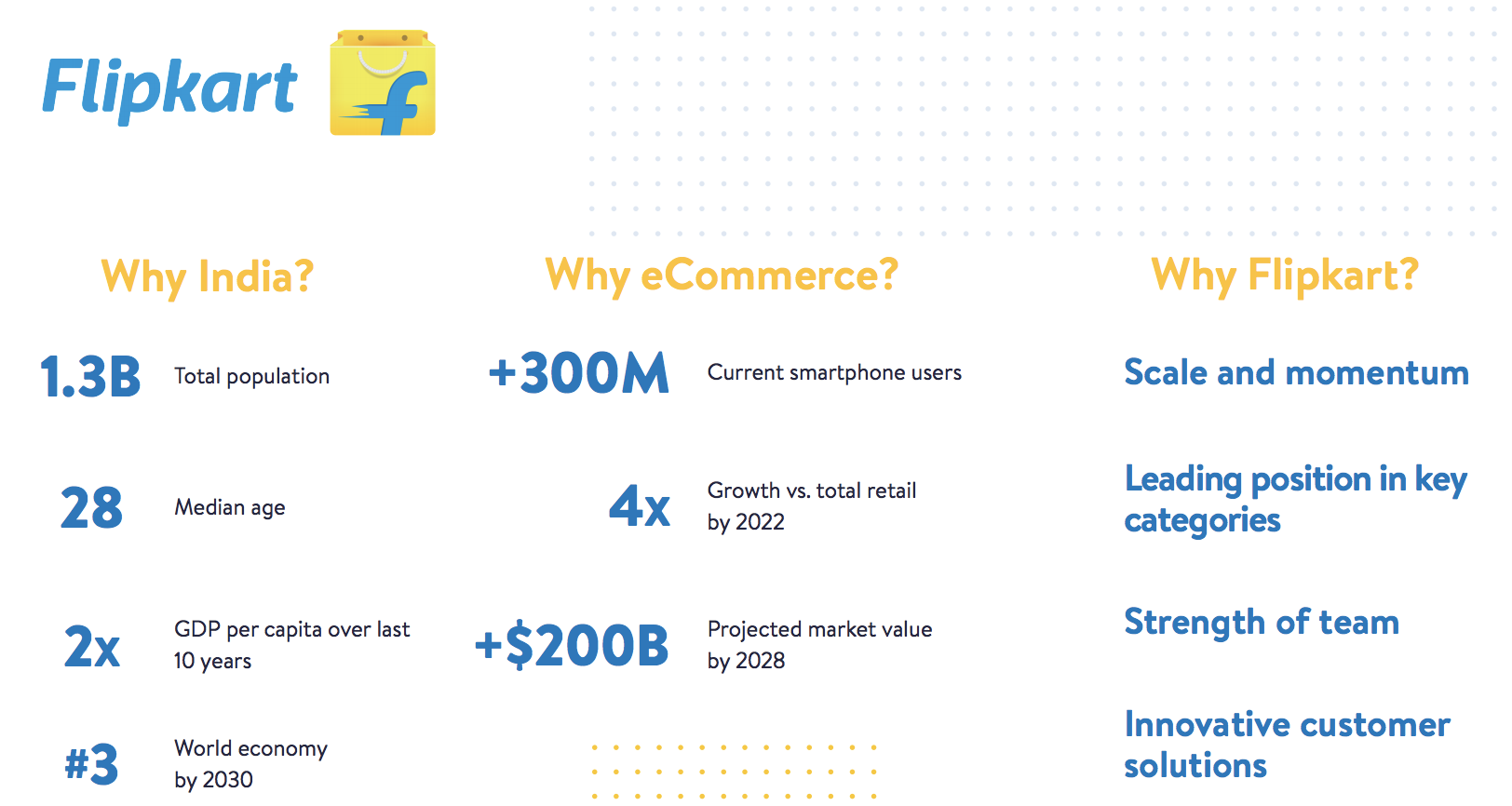

And in early 2018 Walmart agreed to buy 77% of India’s leading online retailer, Flipkart, for $16 billion. Analysts believe Flipkart’s sales could grow at over 30% annually for the next decade thanks to India’s large population, fast-growing middle class, and e-commerce market that’s estimated to exceed $200 billion in annual sales by 2028. At the end of 2018, Flipkart had 80% market share in Indian e-commerce and 64 million customers.

Source: Walmart Investor Presentation

Source: Walmart Investor Presentation

In addition to buying growth via acquisition, a big part of Walmart’s strategic focus is to leverage its greatest strength, a nationwide distribution and logistics supply chain, with the patchwork of new online businesses and brands it has developed. This includes trying to recreate Amazon’s strong focus on convenience.

Walmart Online Convenience Initiatives

Source: Walmart Investor Presentation

Today Walmart offers free two-day shipping (on orders over $35) to 99% of U.S. residents and can ship next day to approximately 87% of the population. It’s also installing automated pickup lockers to allow customers to order online and pick up at the store without standing in line.

The results of Walmart’s online efforts have been impressive with about 40% growth in 2018 and management expected 35% growth in 2019. Analysts expect Walmart’s online sales to grow around 30% a year through 2023 when they are expected to make up approximately 15% of total company sales (including JD.com and Flipkart).

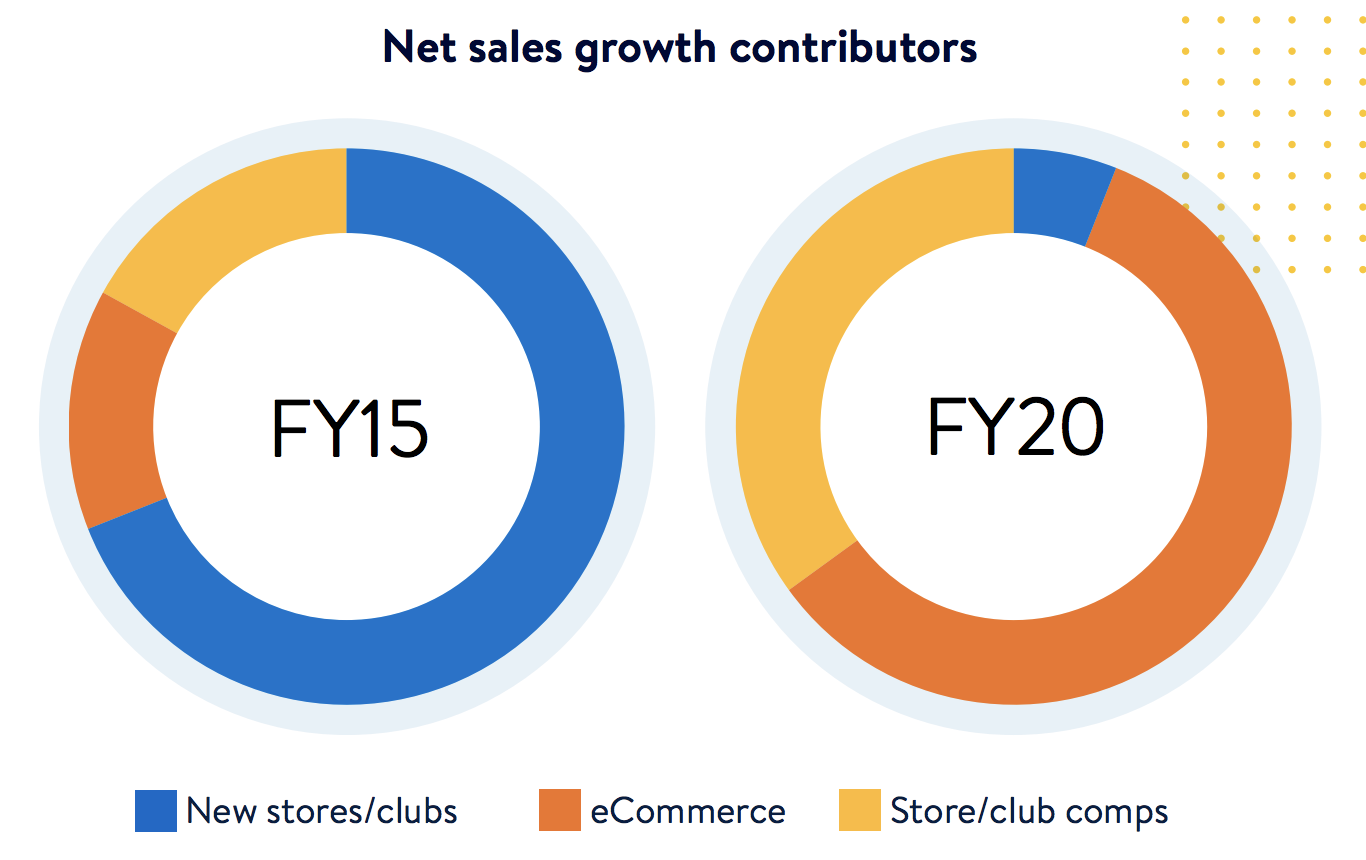

Simply put, over the last five years Walmart’s growth driver has shifted from opening new stores, to maximizing growth in its existing locations and expanding its e-commerce operations.

Source: Walmart Investor Presentation

Source: Walmart Investor Presentation

Walmart’s scramble for a greater share of online sales depends on its ability to integrate its large store footprint with e-commerce operations. In 2018, for example, the company launched online grocery pickup at 1,100 stores in the U.S. and plans to add 1,000 more in 2019. The reason Walmart is so active in expanding online grocery pickup is because this is by far the fastest growing part of the market.

In fact, by 2020 research firm Statista estimates 10% of all U.S. groceries will be ordered online, and then either picked up at the store or delivered, representing a $30 billion market (and 400% growth compared to 2012).

Thanks in part to its focus on the online world, Walmart has turned around its struggling U.S. stores, recording 18 consecutive quarters of positive same-store sales growth through the end of 2018. In fact, Walmart’s growth rate has even accelerated due to the success of its e-commerce integration.

The rest of the firm’s improved growth is due to several factors, including the Walmart’s recent push into upgrading and remodeling many of its stores (better lighting, wider aisles, and lower shelves) and increasing worker wages to lower turnover.

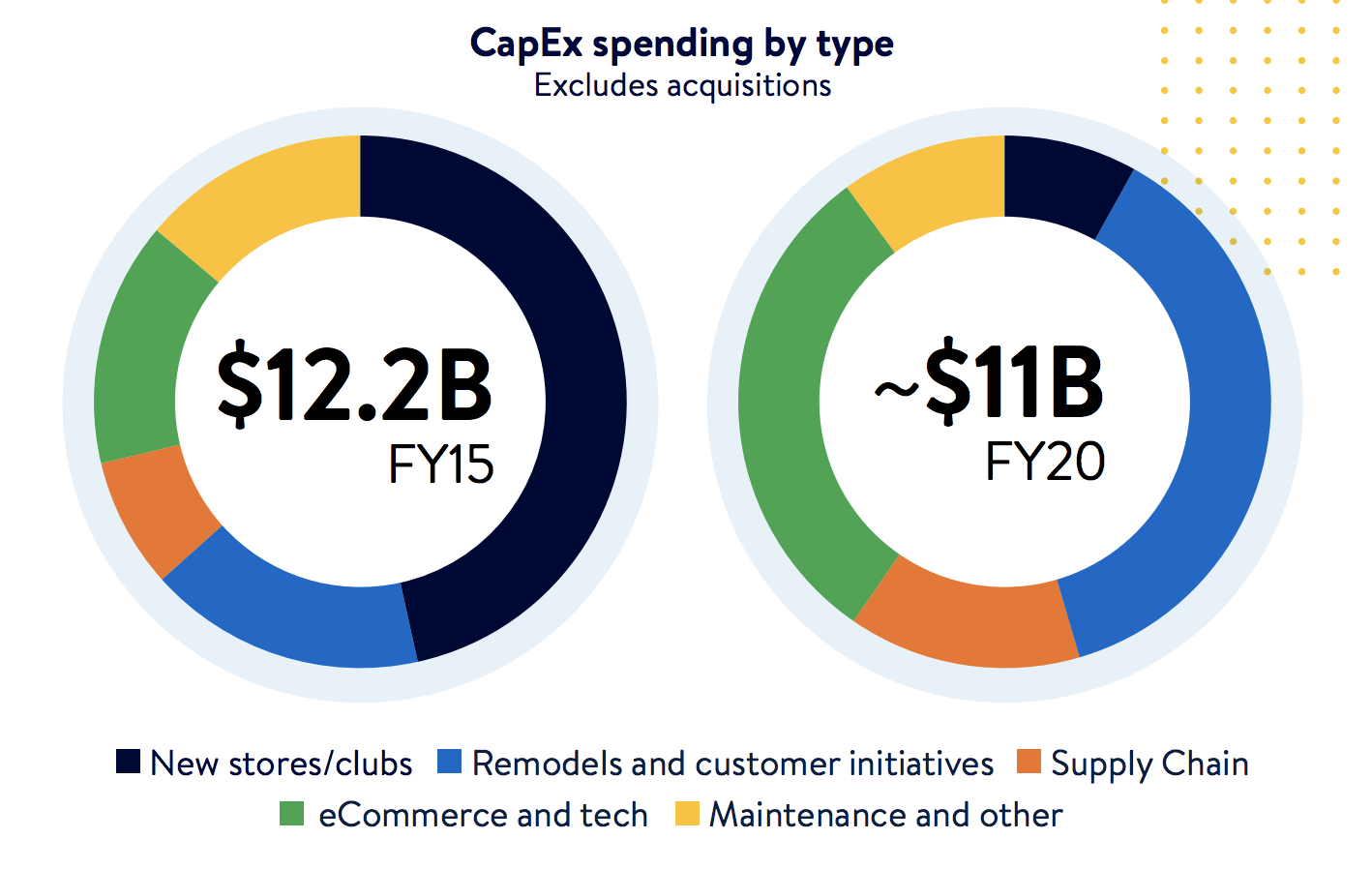

Overall, Walmart has simply become a much more focused company. Management’s improved capital allocation discipline and response to changing consumer shopping habits is demonstrated by the company opening fewer new stores and maximizing the sales from its existing store base, including with ever-larger e-commerce integration.

Going forward, store openings are going to be a much smaller focus for the company, with most new stores being planted in international markets such as China and Mexico. In 2019 management expects to spend $11 billion on capex, with most of that focused on remodeling stores and expanding e-commerce which the company expects to drive most of its sales growth going forward.

Source: Walmart Investor Presentation

Source: Walmart Investor Presentation

Walmart expects its more disciplined approach to capital spending will generate over $20 billion a year in free cash flow going forward, continuing to fuel generous returns of capital to shareholders via dividends and buybacks.

While there is still plenty of work to be done, Walmart appears to be making solid traction on its plans to prove that it can, once again, successfully adapt to a fast-changing retail world and compete on a massive scale.

However, while Walmart has managed an impressive growth turnaround, there remain several risks to its continued success which could suppress its pace of earnings and dividend growth for the foreseeable future.

Key Risks

Consumer retail has always been a cutthroat industry marked by a relatively little customer loyalty. In other words, it’s generally a intensely competitive world characterized by a race to the bottom on price.

This is especially true given that Amazon’s founder, Jeff Bezos, has a “your margin is our opportunity” approach to business. In other words, Amazon’s primary goal isn’t necessarily to maximize profits today but to gain market share by offering a greater number of products and services delivered in an ever-more convenient and affordable manner.

So while Walmart’s online sales are booming, there is no guarantee that it will be able to enjoy even the slim margins it has in the past. Since 2015 the company’s operating margin has shrunk from 6% to 4% in 2018, indicating that its solid growth in online sales isn’t necessarily translating to its bottom line.

Walmart’s profitability seems unlikely to improve anytime soon given what CEO Doug McMillion told analysts on the company’s fourth-quarter 2018 earnings call:

“We fully expect the pace of (e-commerce) change to accelerate in the next five years versus the last five years…We see the future as a frictionless experience across stores and e-commerce, but we have more work to do as customers raise their expectations, competition persists, and the omnichannel retail story continues to evolve.”

That means higher spending on Walmart’s fast-growing but still money-losing e-commerce business. According to Walmart’s CFO Brett Biggs, the company expects its losses in e-commerce to increase in 2019 as it invests more in infrastructure, people, and online grocery.

It is true that Walmart has historically been one of the best retailers in the world at cutting costs via its efficient supply chain, and automation seems likely to only reduce costs further in the future.

However, that doesn’t necessarily mean that Walmart’s margins will find relief. In the highly competitive retail world, over time most cost savings end up being passed on to consumers.

And with nearly 60% of Walmart’s sales from groceries, the company will have to protect its margin against upstarts like Aldi and Lidl, new budget-focused grocery chains that entered the U.S. in recent years and have big growth plans. For example, Aldi is investing $5.3 billion to open 800 new stores by 2022 and plans to have 2,500 stores by then, with aims of becoming the third largest U.S. grocer.

Another challenge for Walmart’s profitability actually stems from its impressive turnaround in the performance of its brick-and-mortar stores. Specifically, the company’s greater focus on a higher paid but better trained and happier workforce won’t come cheap.

Walmart has been raising wages for several years now and in 2018 lifted its minimum starting wage to $11 per hour. Its average U.S. worker now makes $14.01 per hour. However, rival Target has said that by 2020 it will be paying a minimum starting wage of $15 per hour in a similar effort to create a happier workforce that results in lower turnover. Meanwhile, in October 2018 Amazon announced a $15 minimum wage for all of its U.S. employees.

Simply put, market competition could force Walmart’s labor costs to keep rising for several more years, further squeezing its struggling profit margins.

Finally, much of Walmart’s growth potential lies overseas, especially in markets such as China, where it’s opening a large number of new stores, and India, where Flipkart is likely to spend billions growing its online business. These regions have very different consumer cultures, and the company doesn’t have the dominant logistics and distribution infrastructure it enjoys in the U.S.

In other words, Walmart has fewer advantages when it enters a new market in foreign countries. Instead, it’s competing with well-established local giants who have spent decades creating and optimizing their own product mixes and distribution networks.

As a result, Walmart’s overseas stores have lower margins and can experience higher volatility in customer traffic and same-store sales. While trying to recreate its U.S. success around the globe sounds appealing, this expansion strategy is far from guaranteed to be a profitable success story, especially in emerging markets like India.

For instance, Walmart took on substantial debt to fund its Flipkart deal, buying a stake in a business that is still unprofitable. In 2018 Flipkart’s sales were $4.6 billion and its operating loss was about $780 million. Morningstar doesn’t expect Flipkart to break even until 2024, which would mean Walmart’s ownership stake won’t start boosting its own bottom line until 2025 (and only if analyst growth estimates come true).

In other words, Walmart is paying a high price for a fast-growing business which, like its U.S. counterpart, might not see steady profitability for many years.

A number of challenges could arise, especially now that India’s government has imposed restrictive regulations on online sales which might slow Flipkart’s growth. The new regulations prevent exclusive agreements and don’t allow the sale of products from companies they own equity stakes in.

Simply put, whether Walmart tries to grow domestically or abroad, the company faces intense competition from very well-capitalized and nimble rivals.

While Walmart is continuing to prove itself a capable retailer, its slow long-term cash flow growth potential means that this future dividend king’s payout growth is likely to merely track inflation.

Closing Thoughts on Walmart

While the retail world has always been highly competitive, Walmart has done an admirable job adapting to changing industry conditions over the years. That includes an impressive entrance into e-commerce that should help the world’s largest retailer remain relevant in the coming years.

Similarly, the company’s high mix of defensive grocery products and dedication to rewarding dividend investors with 45 consecutive years of payout increases make it a fairly low-risk dividend stock.

With that said, Walmart’s recent success in growing its same-store sales and e-commerce operations has thus far failed to result in anywhere near the bottom line growth it has historically enjoyed. Online sales have compressed the company’s margins while demanding substantial capital investments, and their long-term profitability remains uncertain.

Given the company’s accelerating pace of e-commerce investments, Walmart seems likely to keep raising its dividend at a very modest pace of 2% per year for the foreseeable future.

Overall, Walmart is an interesting dividend aristocrat to watch because of its scale and defensive qualities, but the many challenges the company faces going forward shouldn’t be ignored either. For now, Walmart seems likely to remain a low-growth cash cow that should only be considered when its yield is relatively high.

— Brian Bollinger

Simply Safe Dividends provides a monthly newsletter and a comprehensive, easy-to-use suite of online research tools to help dividend investors increase current income, make better investment decisions, and avoid risk. Whether you are looking to find safe dividend stocks for retirement, track your dividend portfolio’s income, or receive guidance on potential stocks to buy, Simply Safe Dividends has you covered. Our service is rooted in integrity and filled with objective analysis. We are your one-stop shop for safe dividend investing. Brian Bollinger, CPA, runs Simply Safe Dividends and previously worked as an equity research analyst at a multibillion-dollar investment firm. Check us out today, with your free 10-day trial (no credit card required).

Source: Simply Safe Dividends