“It’s really not a good idea to sell anything,” Bill said.

Bill Bonner and I were in Nicaragua for the fifth annual Bonner & Partners Family Office meeting at Rancho Santana. After the conference was over, we went to dinner “off campus” for a change of pace.

In pitch darkness, we drove on unlit dirt roads, dodging the occasional cow. We came upon a little town where some kind of festival was going on, nosing the car past a parting sea of people.

[ad#Google Adsense 336×280-IA]Then we made a wrong turn and had to double back… nose the truck past the crowd again… but we eventually found our spot.

It looked like a shack with some tables and chairs and lights haphazardly set out near the beach.

Bill and I settled in at a table by the water and ordered up a couple of Tonas, the Nicaraguan beer of choice.

We talked about a lot of different things – wealth, money, building businesses, real estate…

During our talk, Bill mentioned that it’s not a good idea to sell anything. Well, not anything. He was talking about good assets.

I agreed. There are taxes when you sell. And fees. And then you have to decide what to do with the money, which you may very well lose in the next investment.

Good assets tend to hold their value and even grow more valuable over time. It’s a lesson I learned all over again when I researched for my book, 100-Baggers: Stocks that Return 100-to-1 and How to Find Them. (In fact, on my list of essential principles, it’s No. 10: “You Should Be a Reluctant Seller.”)

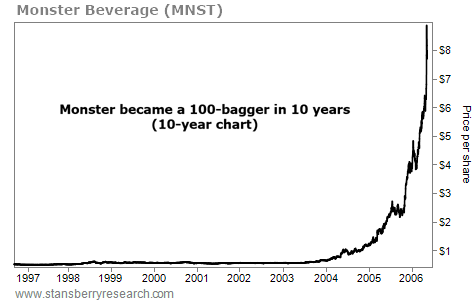

One great example of a good asset to hold for the long term is Monster Beverage (MNST), the famous maker of energy drinks and other beverages…

Monster enjoyed high profit margins and returns on its capital, two marks of a great business.

It became a 100-bagger in 10 years – a remarkable feat that required a 50% annual growth rate. But it fell more than 25% at least 10 times during that run. In three separate months, it lost more than 40% of its value.

Yet if you focused on the business – and not the stock price – you would never have sold. And if you put $10,000 in that stock, you would have $1 million at the end of 10 years.

Yet if you focused on the business – and not the stock price – you would never have sold. And if you put $10,000 in that stock, you would have $1 million at the end of 10 years.

The most stunning gains come when people just leave their stocks alone… And then they wake up shocked by how much they’re worth.

If you don’t need the money, it’s probably best to let your investments ride. Do less, and make more. There are many inspiring examples.

In 100-Baggers, I tell the story of Ronald Read, who was the subject of a Wall Street Journal piece in 2015, “Route to an $8 Million Portfolio Started With Frugal Living.”

Ronald Read was a janitor at JC Penney “after a long stint at a service station that was owned in part by his brother.” So how did he make his money?

He had 95 stocks when he died. Many of these he held for decades. He owned Procter & Gamble (PG), JPMorgan (JPM), J.M. Smucker (SJM), Johnson & Johnson (JNJ), and other blue chips. Not every stock he owned was a winner. But the profits from the winners overwhelmed the losers.

It’s a simple formula. Timeless.

I’ve got a lot of stories like this, some of them from readers. Here’s one:

I remember as a kid my dad used to grumble about my grandmother because she would complain that she couldn’t see well and she had cataracts. He would say, ‘well she doesn’t seem to have any trouble reading the newsprint in the WSJ when she is checking her Esso stock.’ [Esso is a brand of ExxonMobil]. That would have been around 1971 and somehow that is still in the recesses of my mind.

Just consider as a young kid if I had just started accumulating ExxonMobil back then. It would not have taken a genius or much of a stock picker gene. Just buy the largest oil stock in the world that had been around for a hundred years… Just put your blinders on and keep accumulating over a lifetime. No stress, no white knuckles since it has a very conservative balance sheet, no high wire act. So where [sic] would $1 back in 1971 in Esso be worth today? By my calculations $418 plus one would have been collecting a juicy dividend all those years.

Bill is right. It doesn’t pay to sell. Buy the best assets – ones with durable cash flows and potential for growth – and sit.

Sincerely,

Chris Mayer

[ad#stansberry-ps]

Source: Daily Wealth